Blog17: Genealogy of Serial Killers, Cult Leaders, Murderers and Miscreants - Lydia Sherman, the "Poison Fiend"

- Nicole Joseph

- Aug 14, 2025

- 25 min read

Updated: Sep 29, 2025

Trigger Warning: Family Violence, Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, Mental Abuse, Childhood Abuse, Infanticide. Please do not continue if any of the above topics trigger you.

Understanding the Impact of Generational Trauma through Genealogy.

Lydia Danbury Sherman is infamously known as a 19th-century serial killer responsible for the deaths of multiple children—many of whom were her own—as well as three husbands. Yet, such a disturbing narrative raises deeper questions: Why did Lydia, widely regarded during her early life as a devoted wife and caring mother, begin committing these crimes in her 40s?

By examining generational trauma and historical context through genealogical methodology, we may begin to uncover the structural and psychological factors that contributed to such a drastic and horrifying transformation.

Contradictions in Information

Genealogists work with a range of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources to reach evidence-based conclusions. However, inconsistencies are frequent—particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries—where documentation may vary or be absent altogether. Such discrepancies, including contradictions in names, dates, and locations, may be attributed to linguistic barriers, low literacy, shifting political borders, human error, and recordkeeping practices. In some cases, the absence of expected information—known as negative evidence—can be just as telling as the data that exists.

One such challenge arises in tracing the surnames of Lydia and her extended family. Variants such as Danbury, Danberry, Dansbury, Dansberry, and Dansburg appear throughout the records. Even Lydia herself, when interviewed by a reporter about her life, used the spelling Danbury, which appears in earlier family documents. However, the spelling Danberry becomes far more prevalent in Lydia’s generation.

Paternal Grandparents - Brief Summary

Lydia’s paternal grandparents were William Danbury and Mary Snook. Her lineage is deeply tied to the early history of the United States, as William Danbury served three years in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. His service is documented in the U.S. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files [1].

These pensions, granted to veterans and their widows, evolved in eligibility criteria over time. The National Park Service offers a valuable summary of the legislative acts governing Revolutionary War pensions.

At the time of his military service, William Danbury lived in Amwell, New Jersey, near the Pennsylvania border. He later moved within the Trenton, New Jersey area. He married Deborah Cumten on 13 December 1817, also in Amwell, NJ [2].

A Life Marked by Financial Instability

Court records and newspaper archives reveal that William Danbury struggled with chronic debt, a pattern later mirrored in the life of his son, Samuel Danbury, Lydia’s father. A search of the New Jersey Supreme Court Case Files (1704–1844) shows William first sued for debt in 1795 and filed a case against another party in 1799. All remaining cases listed him as the defendant, indicating a prolonged period of financial hardship [3].

A particularly telling article from the Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Advertiser (August 1826) reports that William was imprisoned for debt at the Hunterdon Gaol. Just two days prior, he had participated in a Sheriff’s sale, liquidating five parcels of land. The proceeds were insufficient to satisfy his debts, leading to his confinement [4]. In the article mentioned above, William is listed as confined for debt in the Hunterdon Gaol on August 4, 1826 [5].

This was just two days after he sold everything in a sheriff's sale, including five parcels of land. Since the Sheriff's sale did not generate enough money to cover William's Debts, he was sent to the local jail [6].

Further information about William Danbury emerges from his Revolutionary War pension files. In his initial 1819 application, Danbury, aged 59, reported service as a private in Captain Hurd’s company of the 4th Regiment Dragoons under Colonel Moylan in the Pennsylvania Line. He enlisted on 12 June 1778 and served until his honorable discharge on 20 April 1781. He petitioned for assistance due to “reduced circumstances,” which was granted [7].

While the record above provides limited information, subsequent applications offer further insight into some of the community relationships William had at the time. According to a letter written by Nicholas Danbury on 21 June 1824, William’s pension was suspended, and he was forced to reapply [8].

The 1826 application offers significant detail. It documents a sheriff’s sale of William’s possessions on 11 April 1826 due to unpaid debts, with buyers including Adam, Daniel, and Aolane Danberry, as well as residents Jacob Servis, Andrew Quick, and others. He sold land to Nathaniel Smith and Leonard Neighbor shortly before his incarceration for debt on 4 August 1826. By this time, he was without property and declared unable to work [9].

The application notes William’s health struggles (specifically “dizziness”) and his responsibility for his wife, Deborah (age 33), granddaughter Mary Ungesser (13), and grandsons Peter and William Barney (ages 8 and 3) [10]. The 1830 Federal Census places him in Amwell, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, in a household of six: two male children, three adult males, and one adult female—likely corresponding to the dependents listed in 1826, though some individuals remain unidentified [11].

Together, these records create a caricature of William Danbury—Revolutionary War veteran, impoverished debtor, and caregiver. Notably absent from the documents are his own children, suggesting strained or severed familial ties. While there is no direct evidence of abuse, the instability of William’s later years likely shaped the experiences of his descendants, including his son Samuel.

Maternal Grandfather and Grandfather

Further research is necessary to fully trace the lineage of Lydia’s maternal grandparents, though preliminary findings offer some insight. Available evidence suggests Lydia became estranged from her paternal family following her mother’s death, likely as a result of multiple relocations among extended relatives during early childhood. She did not reconnect with her paternal siblings until adolescence.

A working hypothesis, informed by genealogical records and contextualized through historical sources, posits that Lydia was placed with maternal relatives after her mother’s passing. However, additional local archival research is required to confirm this. Later interviews with Lydia, her siblings, and secondary sources—including a newspaper article and a published biography—indicate that her reference to a “Claygay uncle” was likely a purposeful misdirection. This appears to have been an effort to shield her childhood caretakers, the Clayton family, from public scrutiny following her conviction.

Evidence suggests that Lydia initially resided with a woman she referred to as her “maternal grandmother,” who was, in fact, Mrs. Clayton—the grandmother of the other children in the household, not Lydia’s biological relative. Lydia was living with her maternal aunt, Elizabeth Ruckel Clayton, and her husband, John Clayton [12].

Lydia’s Early Life

The early life of Lydia Sherman is obscured by conflicting accounts and sensationalized reporting. A key primary source, The Poison Fiend!: Life, Crimes, and Conviction of Lydia Sherman (the Modern Lucretia Borgia), Recently Tried in New Haven, Conn., For Poisoning Three Husbands and Eight of Her Children (1873), was authored by George Lippard Barclay and was based on Sherman’s jailhouse recollections as well as what occurred at the trial [13]. The title illustrates the sensationalized nature of this work and should be read critically.

After being convicted, she confessed to poisoning multiple family members. Her confession was published across multiple newspapers and appears in an 1873 confessional, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction . In this account, Sherman claimed she was born near Burlington, New Jersey, on December 24, 1824. She stated that her father, Samuel Danbury (she never names his name), was unable to care for her, sent her to live with an uncle named John Claygay. Lydia recalled a relatively ordinary rural upbringing, attending school for roughly three months each year and receiving kind treatment from her caretakers (14). Her brother’s and sister’s accounts of her early life differ slightly, as do different contemporary newspaper articles.

Details across newspaper articles often diverged, reshaping Lydia’s origin story to suit different moral or narrative ends. Most accounts agree that her mother died when Lydia was between nine months and one year old. Some, like the book Poison Fiend, vere from this narrative, suggesting she was sent away only after her father remarried, allegedly due to conflict with a stepmother [15].

An article in the New Brunswick Daily Times dated April 22, 1872, featured testimony from Lydia’s older brother, Joseph Danberry, and her sister and brother-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Nafey. Their recollections largely align with Lydia’s version, but include key discrepancies. For instance, they claimed Lydia was born in Trenton, not Burlington, and that her mother died roughly a year later. According to Joseph, Lydia was initially taken in by her grandmother and moved to New Egypt, New Jersey (16). Mrs. Nafey added that Lydia first lived with her grandmother in a place called “Houtenville,” where she was subsequently placed in the care of an aunt (17). Both siblings agreed that Lydia was one of four sisters and three brothers. They explained that contact with her was lost for a time, but by 1838, the brothers located her living with an uncle in Camden [18]. Such information has been called into question, since Camden did not exist at the time the brothers found their sister [19]. At approximately 16 years old—though the timeline suggests she may have been closer to 14—Lydia moved to New Brunswick to live with her brothers until she married Edmund Struck.

In sum, the early life of Lydia Sherman resists definitive reconstruction. The contradictions between Lydia’s account, her siblings’ recollections, contemporary newspaper narratives, and modern historical interpretation reflect not only the limitations of the sources but also the broader difficulty of assembling a coherent biography of a 19th-century woman whose life was later refracted through the lens of criminal notoriety.

Modern historian Kevin Murphy, author of Lydia Sherman: American Borgia, has challenged parts of Lydia’s autobiographical claims, questioning the existence of “John Claygay” and suggesting inaccuracies in the place names and guardians she mentioned. He notes that there is no verifiable record of a “John Claygay,” casting doubt on Lydia’s stated guardian. He argues that based on the 1830 census, it appears Lydia resided with the Claytons, specifically the Widow J. Clayton in Monmouth County, New Jersey. John Clayton and his wife Elizabeth are listed on the census as well. We see that there are several children residing with them, including a female who would have been Lydia's age [20]. Additionally, Murphy suggests that the location referred to as “Houtenville” was likely a misremembering of Hornerstown, a village near New Egypt where the Clayton family resided [21].

In sum, the early life of Lydia Sherman is obscured by conflicting narratives—her own, those of her siblings, contemporary sources, and modern scholarly interpretation. Together, they paint a picture not only of a mysterious upbringing but also of the challenges inherent in reconstructing a 19th-century female biography from fragmented, contradictory sources.

Why the Clayton Family?

There is some evidence from her grandfather, William Danbury’s Revolutionary War Pension Petition in 1825, that provides possible insight into why Lydia was sent to live with her uncle. According to Leonard Neighbor, a neighbor of Williams, in an affidavit dated 4 February 1825, William was in debt to Mary Carnitage for two burials that cost $137.50 each [22]. This date appears to be around the same time that Lydia’s mother would have passed away, though we would expect it to be later in 1825 if she died 9 months to one year after Lydia’s birth in December 1824. This is just one of many accounts that William and his associates provided, explaining William's financial hardships.

Lydia’s father, Samuel Danbury, faced financial hardships as well. He was a butcher in Trenton and possibly felt overwhelmed having to care for 8 children when his wife died. It is interesting to note that in the 1850 Census, a young boarder by the name of Georgiana Fleeman resides with him and his family [23].

Lydia Sherman and Edward Struck

While residing with her brother, Ellsworth, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, Lydia's sister-in-law was training her as a tailoress, which she ultimately found boring and ended up working for Mr. Owen at the local Methodist Church. Her Methodist class leader acquainted her with Mr. Edward Struck, a widower with six children (24). They were married and together for 18 years.

According to the 1840 U.S. Federal Census, Edward Struck was residing in North Brunswick, Middlesex County, New Jersey. His household included himself, his wife, and five children. Struck reported his age as between 20 and 30 years [25]. Notably, on the preceding census page, Ellis “Ellsworth” Dansbury—identified as Lydia Sherman’s brother—is also listed, suggesting geographic proximity among family members during this period [26].

The earliest record to document Lydia Danbury in connection with the Struck family is the 1855 New York State Census, which provides a comprehensive demographic snapshot of the household. In this enumeration, Edward Struck is recorded as a 42-year-old blacksmith, and his wife, Lydia, as 28 years of age—suggesting a birth year of approximately 1827, if the census data are accurate. Edward’s place of birth is given as New York, while Lydia’s is recorded as New Jersey. The couple’s children are listed as Cornelia M. (age 15), Cornelius (age 12), Lydia (age 7), John (age 5), George (age 4), and Ann Eliza (age 2) [27].

From this information, it may be inferred that Edward’s first wife had died before his marriage to Lydia. Correlating these data with Lydia’s later jailhouse account suggests that she was approximately 22 years old when she married the then-30-year-old Edward, around 1846. Some historical accounts, however, state that she was only 19 at the time of marriage, creating a chronological inconsistency. Edward’s occupation is consistently recorded as “blacksmith,” and he is described as a natural-born citizen. Notably, Cornelia and Cornelius—Lydia’s stepchildren—were both born in New Jersey, while the younger children were all born in New York [28].

The 1860 Federal Census offers additional insight into the Struck household. Edward, aged 52, is recorded as a policeman, while Lydia, aged 33, is listed with no occupation—an omission that, in the context of the period, typically signified a role has a housewife. Once again, the census data suggest a birth year of approximately 1827 for Lydia. This conflicts with other sources: contemporary newspaper accounts report that Lydia was 19 at the time of her marriage to Edward, and in her own statements she gave her date of birth as December 24, 1824. Thus, both the 1855 and 1860 census enumerations yield an estimated birth year inconsistent with her reported age and self-reported birth date [29].

The only outstanding children were Josephine, who was born after the census was taken in 1855 and died in 1857, and William, who was not born until 1863 and will meet his unfortunate end in infancy.

The Strucks through Lydia’s Narrative

Lydia’s later recounting of her life with Edward would be that of a normal family. She attended church regularly and devoted herself to raising the children, while Edward worked in his trade as a blacksmith. For approximately a decade, they lived as a typical working-class household in Carmansville, New York, located in northern Manhattan. Edward abandoned his trade and entered public service as a police officer, relocating the family to Manhattanville, New York, where he joined the New York Metropolitan Police. This transition occurred between 1855 and 1860 [30].

According to Lydia’s later testimony, her life with Edward Struck remained happy until his dismissal from the police force, after which he became markedly depressed and sullen. She recounted that, during one of his patrol shifts, a violent altercation erupted in a saloon located on his beat. Contemporary reports from hotel staff alleged that Edward failed to intervene, resulting in the death of a detective. Lydia contested this characterization, asserting that Edward had been some distance away at the time of the incident and had not fled the scene out of cowardice, as claimed by the witnesses. Nevertheless, Struck was immediately placed on leave and ultimately discharged from the force [31].

Lydia stated that the loss of his position plunged Edward into a severe depression, leaving him unable to work, and that he implored her to end his life. She further claimed that a fellow officer, who resided in the same building, advised Edward to ingest arsenic to spare both himself and his family further hardship. Lydia later admitted that she could not envision raising the children alone and believed they would be “better off dead.” Significantly, her recollection introduced the detail that an authority figure—a fellow officer whose name she could not recall—had recommended the very substance she would later employ in the deaths of multiple members of her household [32].

The question of why a 40-year-old, seemingly well-adjusted lady would kill her husband and children invites examination. The pattern of events suggests what might be described as “death by convenience,” in which decisions appear to have been guided primarily by considerations of economic contribution from Lydia’s perspective. Accounts of the deaths differ between sources. Most accounts list Edward Struck as the first to die, succumbing to arsenic poisoning on 26 May 1864 [33].

In July of 1864, according to some accounts, three of the couple’s younger children—Martha Ann (age 6), Edward Jr. (age 4), and William (age 9 months)—also died. Lydia reportedly justified these killings by reasoning that the children were too young to contribute economically to the household and were, in her view, “better off dead.” Official causes of death were recorded as remittent fever for Martha Ann and Edward Jr., [34] and bronchitis for William [35]. Notably, there was no mention of William in Lydia's Confession, and he appears separately from Martha Ann and Edward in the Manhattan Death Registry. The only William Struck recorded in the Manhattan Death Registry died of bronchitis on 10 March 1865, which would appear in contemporary newspaper reports from the 1870s. His address was listed as 121 Norfolk instead of 128 S 10th Ave., which is only 2 miles away from each other, and she had moved following her husband's death. Still, the same doctor came to call, and he too was buried in Trinity Cemetery. This William Struck is listed as being 9 months,15 days old [35]. During Lydia's confession, she emphatically states that she does not remember dates, but she does not seem to forget entire children.

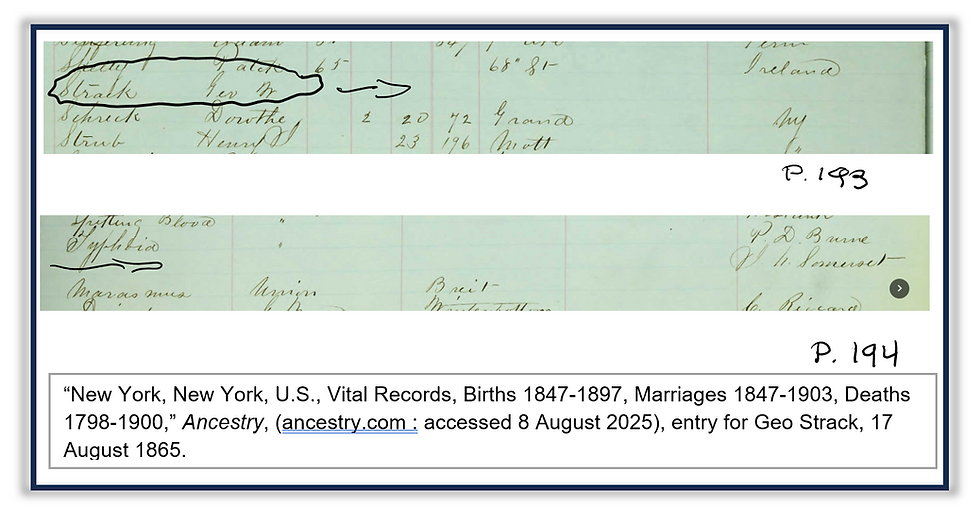

The couple’s older son, George Whitfield, initially avoided the same fate because he was employed as a painter’s apprentice, earning a modest stipend that contributed to the family’s income. However, when George developed painter’s colic—a form of lead poisoning associated with occupational exposure—he was rendered unable to work. Shortly thereafter, Lydia poisoned him as well [36]. There is no George Whitfield Struck listed with details in the Manhattan Death Registry, but the following name does appear on the August 17, 1865 date. Could this be George Whitfield Struck [37]?

This left Lydia, her namesake, and little Ann Eliza. She believed that she and her daughter Lydia would be able to provide for themselves if little Ann Eliza was out of the picture. Ann Eliza was described by Lydia as “the happiest child I ever saw” [38]. She would die next. After all, Lydia worked at a dry goods store part-time and thus helped with financial support. Due to distance, young Lydia was unable to continue working and quit. She died on 19 May 1866, though Lydia claims it was a natural death [39]. Interestingly, she did not pass away until she was no longer working. Lydia told a reporter in 1875 that her “victims would be better off in another world" [40]. Eight family members were struck dead between 1857 and 1866. Lydia confessed to being responsible for the deaths of 5 family members. Nobody found any of these deaths suspicious and death records list many of the common causes of death at this time as the Strucks' causes of death. After all, it was common for people to succumb to disease and fevers.

Lydia and Dennis Hurlburt

Following eighteen-year-old Lydia's death, Lydia Sherman sought to support herself as a housekeeper and nurse and. For a short period, she relocated to Pennsylvania with her eldest son, John—the only surviving child—where they resided with Gertrude, Edward Stuck's daughter, and her husband. The farm life did not work out for her though she argued that she was not paid what was due to her [41].

Upon returning, Lydia worked in a sewing machine establishment where she met Mr. James Curtiss and secured a position as housekeeper for Mr. Curtiss’s elderly mother in Stratford, Connecticut, a role she held for eight months [42]. She subsequently entered the employ of Mr. John Fairchild, who maintained a household for Dennis Hurlburt, a widower 28 years her senior. After a brief courtship, Lydia married Mr. Hurlburt on 22 November 1868 [43].

According to Lydia, the marriage was harmonious for its first four months. She claimed that Hurlburt began experiencing dizzy spells and, three months into the marriage, altered his will to transfer all assets to her, citing fears for his health. On 20 January 1870, Hurlburt died of what was later determined to be arsenic poisoning. Lydia initially attributed his illness to a meal of clams and cider mixed with saleratus, asserting that he had insisted she drink the cider as well, after which she herself became ill and vomited [44].

Lydia and Horatio Nelson Sherman

Only two months after the death of her husband, Dennis Hurlburt, Lydia would meet her next husband, Horatio N. Sherman, known to the community as Nelson. Nelson and Lydia were both born in 1824. He was a widower in charge of a young baby and needed a housekeeper. Two weeks after Lydia moved in, he offered to marry her, but Lydia said she needed more time. During this time, Nelson helped find a tenant for Lydia's farm [45]. Soon thereafter, on 3 September 1870, Horatio and Lydia Sherman were married in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, at Horatio's sister's house [46].

According to Lydia, Nelson told her that he wanted Frankie, his baby, to die. Lydia complied and put arsenic in the baby's milk. Frankie died 15 November 1870, at 10 months old [47]. Lydia stated that following Frankie's death, Nelson began to drink heavily. Lydia claimed she had to loan Nelson $600 at this time to support the family due to Sherman's poor money management [48].

Another stepchild of Lydia, Ada, would meet an early end from arsenic poisoning. Lydia later stated that she had been covering the cost of Ada's clothing and that the girl fell ill on Christmas Eve 1870, just over one month after the death of Frankie. According to Lydia’s account, her husband requested $10 to pay a physician, but she refused to give him the money directly, opting instead to pay the doctor herself. She claimed that her husband’s anger at this refusal provoked her to lace Ada's tea with arsenic. Addie died on 31 December 1870 at the age of fourteen [49].

Mr. Sherman continued to drink, according to Lydia. There was one Sunday when he went out drinking and returned very drunk, so she put arsenic in the pint of brandy he had in the house. Lydia never confesses to knowingly killing him and argues that she did not mean to kill him. She wanted him to develop an aversion to liquor. Horatio Sherman died on 12 May 1871 [50].

The Investigation/ Trial - Summary of Barclay's Work

Investigation

Mr. Sherman and Mr. Hurlburt's bodies were exhumed, so chemical tests to find arsenic could be completed. The contents were analyzed in a lab in New Haven, Connecticut, where the body's contents tested positive for arsenic. Ada and Frankie's bodies would also be examined [51]. A warrant was then issued for Lydia for the murder of Horatio Sherman. She was arrested in New Jersey, but was brought back to Connecticut to stand trial. She was arraigned on this indictment on 21 September 1871 [52].

Not everyone was ready to have their family member's bodies exhumed. John Struck, Edward Struck's son, opposed exhuming his family members even though his half-brother, Cornelius Struck requested they be examined [53].

Indictment

While the past deaths were now being investigated, the only charges related to the death of a family member were those related to the death of Horatio Sherman, which she never confessed to. Prior to the trial, many of her friends and family visited her as they were sure she was innocent of this crime.

Trial Evidence

Arsenic was located in the livers of Nelson H. Sherman and Dennis Hurlbut. Mr. Hurlburt also had a substantial amount of arsenic in his stomach [. Most of the evidence would be circumstantial.

Trial

The prosecutor is Mr. Foster and her defense attorney is Mr. Waterous. Lydia pleads not guilty. The prosecution is trying to prove criminal intent and show that Lydia had access to arsenic. The defense wanted to prove that the evidence against Lydia was inadmissible and wanted to show Lydia in a positive light.

Timeline of Mr. Sherman's Illness based on witness and professional testimony - May 1871

Monday, May 7

Severe headache

Onset of additional symptoms (see May 8)

Tuesday, May 8 (First Doctor’s Visit)

Nausea and vomiting

Parched mouth and throat

Great thirst

Sharp stomach pain

Racking bowel pain

Hot, dry skin

Quick pulse and faintness

Later: loss of voice, persistent hawking, and choking

Wednesday, May 9

Temporary reduction in vomiting and thirst

Thursday, May 10

Condition worsened significantly; appeared terminal

Cold extremities and body

Pulse imperceptible

Complaints of faintness

Burning stomach pain

Friday, May 11

Livid skin, especially under the eyes

No purging, delirium, or convulsions (typically associated with arsenic poisoning), though most other symptoms were consistent with arsenic poisoning

Saturday, May 12

Death of Sherman

Brief Trial Summary

Day 1: 16 April 1873

Lydia Danbury was read the indictment and was arraigned; plead not guilty

Dr. Ambrose Beardsley (local doctor) of Derby called to testify on Nelson Sherman's symptoms

Day 2 – 17 April 1873

Dr. Ambrose Beardsley reexamined: reiterated symptoms.

Nelson "Nellie" Sherman (son, age 21): testified Lydia delayed him from seeing his father.

Dr. Kinney (knew Sherman for 18 years): confirmed symptoms seen on May 11, 1871, consistent with arsenic poisoning.

Day 3 – 18 April 1873

Dr. Gould A. Shelton: discussed poisonous properties of bismuth.

Mrs. Sherman (mother of deceased):

Met Lydia at Addie’s funeral; Lydia made threatening comment about leaving her son.

Visited son before death; he fainted after tea, hid wallet from Lydia.

Lydia retrieved the money and gave only $5 to "Nellie" out of $105.

Ellen Harrington: believed Sherman and Lydia treated each other properly.

George Peck (druggist in Birmingham): Lydia purchased arsenic in spring 1871 for rats.

Prof. George G. Barker: found 5 grains of arsenic in Sherman’s liver.

Day 4 – 19 April 1873

Prof. Barker: gave in-depth forensic testimony on arsenic toxicity and concentration.

William Ford (fellow officer): saw Sherman the Sunday before death—no alarming symptoms observed.

Day 5 – 23 April 1873

William S. Downes (coworker): worked with Sherman the Monday before illness—he seemed healthy.

George W. Sherman (brother):

Lived intermittently with the couple.

Testified about marital conflict and separate sleeping arrangements.

Heard Lydia complain Sherman didn’t love or respect her.

Said Lydia mentioned Sherman ate reheated fish and drank chocolate before death.

Orrin Lathrop: saw Sherman Monday before death; appeared pale and nauseated.

Mary Jones (deceased wife's mother-in-law): testified about Addie’s death and related timeline.

Dr. Beardsley: continued testimony on arsenic and bismuth.

Day 6 – 24 April 1873 (Defense Begins)

Mr. Waterous (defense counsel):

Claimed Sherman was drinking heavily before illness.

Argued Lydia was attentive, caring, and innocent.

Asserted arsenic was purchased solely for rat problems.

Doctors couldn’t definitively conclude cause of death.

Lewis D. Hubbard:

Lived with Shermans for 12 years.

Saw Sherman deteriorate; heard conversation about Lydia caring for Nattie.

Confirmed prior rat issues.

Rev. Leonidas B. Baldwin:

Visited Sherman three times while sick.

Stated Lydia’s conduct was appropriate.

Ichabod D. Allen:

Knew Sherman 15–16 years; testified he could be despondent when drunk.

Mrs. Lewis D. Hubbard:

Lived in same house during illness; described Lydia as kind and helpful.

Confirmed rat infestation in household.

Philip Meyers:

Saw him the Sunday before his death and stated he did not appear to have been drinking at 4 pm

Day 7, Thursday

Lydia Sherman:

Wept briefly at the start of the day.

Col. Wm. B. Wooster (Prosecution) – 1 hr 45 min Argument

Urged the jury to protect society from such crimes.

Emphasized family losses (Mrs. Jones’s and the Shermans’).

Unified expert testimony: cause of death was arsenic poisoning.

Dismissed defense claims about issues with evidence containers (muslin, jar, box) as distractions.

Rejected the defense’s bismuth poisoning theory—experts ruled it out.

Argued suicide was implausible: Sherman resumed normal activities (work, supper, auction) just before falling ill.

Discredited defense’s reference to past “spells”—only one noted on Dec. 9.

Highlighted inconsistent defense testimony (especially from Mrs. Hubbard).

Mr. Gardener (Defense) – 63 min Argument

Emphasized affection between Lydia and Mr. Sherman.

Claimed Lydia helped him fight alcoholism.

Questioned why Lydia would openly buy arsenic if she planned murder.

Noted that Sherman entrusted Lydia with custody of his son.

Mr. Foster (State Prosecutor)

Jury could consider 2nd-degree murder if not 1st-degree.

Pointed to sequence: Sherman was well, ate food from Lydia, fell ill, and died—poison was found.

Claimed motive stemmed from marital strife.

Cited Lydia’s cold or indifferent behavior.

Mr. Waterous (Defense)

Claimed no proof of guilt from the prosecution.

Denied Sherman died of poisoning.

Criticized Dr. Beardsley for not treating Sherman for poison; gave blue pills and morphine instead—called it medical neglect if poisoning was suspected.

Claimed no arsenic was found in the stomach; if it was, it must have been suicide.

Day 8 - Verdict

The judge reminded the jury they could convict on 2nd-degree murder.

50 minutes later, the jury returned a verdict:→ Guilty of Murder in the Second Degree→ Sentence: Life imprisonment

Lydia’s reaction in court:

Pressed her hand to her forehead, sat beside her son.

Moments later, appeared composed and spoke calmly with friends.

Note: An acquittal would have led to another trial in Fairfield County for the poisoning of her previous husband.

After Court

Lydia's composure collapsed and she broke down, expressing deep disappointment with the verdict.

One Last Attempt at Freedom

Lydia Sherman feigned illness and feebleness while in the prison as a means to keep a low profile. The matron, the person in charge of the female prisoners, would say, "good night" and listen for a response to ensure individuals were in their cells, but the matron was used to Lydia not responding since she was so feeble. Another poor practice was that the matron would sometimes failed to lock the door leading out of the main floor, the floor Lydia was housed on. On the night of Lydia's escape, Lydia hid and waited until the matron was on the upper floor and fled. She would later be found in Providence, Rhode Island, and would be returned to the prison, where she would live out the rest of her life [54].

Source References

[1] "United States records," images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9XB-XSSY?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 697 of 898; William Danbury.

[2] "Hunterdon, New Jersey, United States records," images, FamilySearch (https:// www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-1Z9B-LJ?view=index : accessed Jan 3, 2025), image 217 of 800; New Jersey. County Court (Hunterdon County).

[3] "Supreme Court Case Files, 1704 - 1844" database index, New Jersey State Archives, (https://wwwdnet-dos.nj.gov/DOS_ArchivesDBPortal/SupremeCourt.aspx accessed 21 April 2025), search result for entry William Danbury.

[4] "Hunterdon, New Jersey, United States records," digital image, FamilySearch (https:// www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY4-N769-M?view=fullText : Mar 17, 2025), image 371 - 372 of 783; William Danbury.

[5] "Notice to Creditors," Hunterdon Gazette and Farmers Advertiser,Flemington, New Jersey, 23 Aug 1826, News, Digital Image; genealogybank.com (https://www.genealogybank.com : accessed 22 Jan 2025), citing original p. 3.

[6] "United States records," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9XB-XSSG?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 706 of 898; William Danbury.

[7] "United States records," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9XB-X9BF?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 699 - 700 of 898; William Danbury.

[8] "United States records," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHK-Y7MP-YL6L?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 5 – 7 of 17; Nicholas Danbury. and "United States records," digital image, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9XB-XS97?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 710 of 898; William Danbury.

[9] "United States records," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9XB-X9BF?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image 699 - 700 of 898; William Danbury.

[10] Ibid.

[11] 1830 United States Federal Census, database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058/: accessed 31 January 2025), entry for William Danberry, Amwell, New Jersey.

[12] Kevin Murphy, Lydia Sherman: American Borgia (Rocky Hill, CT: Shining Tramp Press, 2013, Kindle Edition).

[13] George L. Barclay, The poison fiend! life, crimes and conviction of Lydia Sherman, recently tried in New Haven, Conn., for poisoning three husbands and eight of her children , online pdf ed., Retrieved from the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/ca19000565/ : accessed 15 January 2025(Philadelphia: Barclay & co, 1873).

[14] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 5.

[15] George L. Barclay, The poison fiend! life, crimes and conviction of Lydia Sherman, recently tried in New Haven, Conn., for poisoning three husbands and eight of her children , online pdf ed., Retrieved from the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/ca19000565/ : accessed 15 January 2025(Philadelphia: Barclay & co, 1873), p.19.

[16 ] "Lydia Sherman’s Crimes," The Sun, New York, NY, 8 July 1871, News, Digital Image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-sun-lydia-shermans-crimes/178389209/ : accessed 21 March 2025), citing original p.1.

[17] Ms. Nafey “The Sherman Trial,” New Brunswick Daily Times, New Brunswick, NJ, 22 April 1872, News, Digital Image, New Brunswick Free Public Library Online (http://newbrunswick.archivalweb.com/imageViewer.php?i=456956&v=r%3D631%26in%3D378%26w%3D880 : accessed 6 February 2025), citing original p. 3.

[18] "Lydia Sherman’s Crimes," The Sun, New York, NY, 8 July 1871, News, Digital Image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-sun-lydia-shermans-crimes/178389209/ : accessed 21 March 2025), citing original p.1.

[19] Kevin Murphy, Lydia Sherman: American Borgia (Rocky Hill, CT: Shining Tramp Press, 2013, Kindle Edition) p. 360 of 3307.

[20] Kevin Murphy, Lydia Sherman: American Borgia (Rocky Hill, CT: Shining Tramp Press, 2013, Kindle Edition) p.2775 of 3307 and 1830 United States Federal Census, database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058 : accessed 6 May 2025), entry for John Clayton and Widow J. Clayton, Monmouth, Upper Freehold, New Jersey.

[21] Kevin Murphy, Lydia Sherman: American Borgia (Rocky Hill, CT: Shining Tramp Press, 2013, Kindle Edition) p.333 of 3307.

[22] "United States records," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9XB-XSSG?view=explore : accessed Aug 7, 2025), image713 of 898; William Danbury.

[23] 1850 United States Federal Census, database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054: accessed 25 November 2024), entry for Samuel Dansbury, Nottingham, Mercer County, NJ.

[24] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 5.

[25] 1840 United States Federal Census, database with images, Family Search ("United States, Census, 1840", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XHRG-85T : accessed on 16 July 2025); entry for Edward Struck, East Brunswick, Middlesex, New Jersey.

[26] 1840 United States Federal Census, database with images, Family Search ("United States, Census, 1840", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YB4-1TL?view=explore : accessed on 16 July 2025); entry for Ellis Dansbury, East Brunswick, Middlesex, New Jersey.

[27] 1855 United States Federal Census, database with images, Family Search (https://www.familysearch.org/ark/61903/3:1:33S7-9BPY-94QQ?view=index : accessed on 6 February 2025); entry for Edward and Lydia Struck, New York County, New York, New York.

[28] ibid., and Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 5.

[29] 1860 United States Federal Census, database with images, Family Search (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GBSH-SJ2?view=index : accessed on 6 Feb 2025); entry for Edward Struck and Lydia Struck, New York County, New York, New York.

[30] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 6.

[31] ibid. p. 7.

[32] Ibid. p. 10.

[33] “New York, New York, U.S., Vital Records, Births 1847-1897, Marriages 1847-1903, Deaths 1798-1900,” Ancestry, (ancestry.com : accessed 8 August 2025), entry for Edward Struck, 1864.

[34] Trinity Cemetery "New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2WHZ-MP5 : 3 June 2020), Edward & Martha Ann Struck, 1864.

[35] “New York, New York, U.S., Vital Records, Births 1847-1897, Marriages 1847-1903, Deaths 1798-1900,” Ancestry, (ancestry.com : accessed 8 August 2025), entry for William Struck, 10 March 1865.

[36] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p.12.

[37] “New York, New York, U.S., Vital Records, Births 1847-1897, Marriages 1847-1903, Deaths 1798-1900,” Ancestry, (ancestry.com : accessed 8 August 2025), entry for Geo Strack, 17 August 1865.

[38] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 13.

[39]ibid. p. 14.

[40]Quote

[41] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p.

[42] Ibid., p. 15.

[43] Ibid., p. 16

[44] Ibid., p. 16 – 19.

[45] Ibid., p. 21

[46] Ibid., p.46 & New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915 "Massachusetts, U.S., Marriage Records, 1840 - 1915," database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2511/ : accessed 13 Oct 2024), entry for Lydia Danbury and Horatio Sherman, 15 September 1870, img 690 of 1091.

[47] Sherman, Lydia, Lydia Sherman : confession of the arch murderess of Connecticut : bloody deeds perpetrated with a cold heart, numerous poisonings, trial and conviction, T.R. Callender, Philadelphia 1873, online pdf Retrieved from Gale Primary Sources (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=MOML&u=ed_itw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CF0102948796&asid=1754697600000~0e94c644 : accessed 24 January 2025), p. 23.

[48] Ibid., p. 24.

[49] Ibid., p. 25.

[50] Ibid., p. 28.

[51] George L. Barclay, The poison fiend! life, crimes and conviction of Lydia Sherman, recently tried in New Haven, Conn., for poisoning three husbands and eight of her children , online pdf ed., Retrieved from the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/ca19000565/ : accessed 15 January 2025(Philadelphia: Barclay & co, 1873). P. 26.

[52] Ibid., p. 27.

[53] Ibid., p. 27.

[54] "Mrs. Lydia Sherman, Her Arrest in Providence Yesterday," Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, 6 June 1877, News, Digital Images, Newspapers.com, (https://www.newspapers.com/article/hartford-courant-1977-arrest-in-providen/157071866/ : accessed 13 October 2024), citing original p.2.

Comments